February 18, 2014 The Future of Product Design

In today’s kitchens, old-fashioned workhorses such as strainers and juicers are rarely used. Fruit juice comes presqueezed in bottles, or worse yet, in cans of concentrate. Vegetables, unless grown at home, are washed long before they hit grocery store shelves. But it is the elegant simplicity of these little-used utensils that product designer Ryann Aoukar admires.

“The intelligence is in the form,” he says. “If you change the form, they no longer function. I wondered how I could update these tools in a smart and aesthetically pleasing way.”

His solutions are so sleek and beautiful, they seem destined for a museum of modern art gift shop: an oval salad bowl with a built-in juicer and seed catcher whose concave back acts as a handle, and a bowl whose handle is also a hybrid strainer and funnel.

“These objects are more up to date to fit today’s life—and more thoughtful. They house two or three objects in one, and they serve us in a simple, basic way,” Aoukar says.

Elegant simplicity is the hallmark of much of his work. Spending twelve years in the private sector, he designed a desk lamp for Luxo/GLAMOX and the interiors of the China Stock Exchange with the Office of Metropolitan Architecture.

When he joined the College of Architecture and Design in 2010, Aoukar brought with him several patented product designs. But with newfound time and resources to do research, he has turned his creativity to investigating new and improved fabrication methods.

Fast and Frugal Fabrication

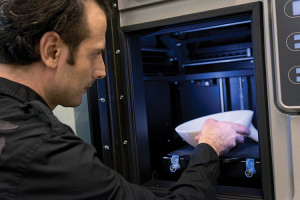

“Normally when you make an object, you lose a lot of time and material during testing,” Aoukar says. “With the 3-D printer, you first perfect the drawing. Then when you send it to the printer, it prints it exactly. Suddenly I don’t need industrial support. I am my own designer, fabricator, and delivery.”

Not all of Aoukar’s work is destined for the kitchen. He also has designed two chairs. Inspired by sitting as a child in his father’s embrace, one is a sleekly wound ribbon of back support that broadens to comfortable seating on a pedestal. The other is a graceful easy chair that seems cut from a column. These polystyrene prototypes were made using UT’s five-by-ten-foot computer numerical control (CNC) machine, which works with mind-boggling speed and precision.

“Traditionally, if you wanted to make a prototype chair, you needed a carpenter, a woodworker, upholsterers, and so forth. It would take two or three months,” Aoukar says.

Creating a prototype can often financially destroy a project before it even has a chance to take off.

“With the CNC, I can design a chair, send the digital file to the machine, and in a couple of hours the chair is cut. This was unthinkable a couple of years ago! And for me, it’s life changing. I can test something in less than a day.”

Environmental conservation is a matter of reducing, reusing, and recycling. Aoukar’s work follows the minimalist approach of reducing, or using as little material as possible.

“We are not recycling garbage, just trying not to make garbage in the first place. It’s a better way. By thinking smart we save energy, the earth in general, and our lives,” he says.

Generating Interest

In June of 2012, Aoukar trucked his prototypes to the International Contemporary Furniture Fair in New York City, where they drew far more attention than he expected. “Lots of people wanted to buy them, but I only had prototypes. They handed me their business cards and said, ‘When you move into production, let us know.’”

With this encouragement, he initiated the next step—but not in a traditional way. Using the crowdfunding website Kickstarter, he shopped his prototypes directly to the public in an effort to raise $30,000 for injection molding equipment needed to produce his product line. For a pledge of $5, $50, or more, investors can receive the item they’ve financed.

“First, I will have to reach $30,000 in pledges, then buy the equipment, produce, and deliver within the agreed-upon time of four months,” he says.

Aoukar hopes his Kickstarter project reaches its goal, but not for the common reasons of fame and fortune. “I want to sell because I want to see how far I can go with the digital process and reducing steps,” he says. “If I’m successful, I will have produced a product for the market in about five steps, whereas before I needed about twenty-five steps.”

For his kitchen objects, he has another motivation that is as ancient as civilization. “When people prepare food, there’s a ritual around it. We need this kind of object that can bring us back to making things, to being more conscious about what we do, and to cultivating our ceremonial communication between people.”

Tools such as computers make our lives simpler, but they can make us feel like machines as we struggle to input the right data in the right way. Aoukar’s simple, efficient products, on the other hand, put us in control of great beauty. Now life is just better.

SOURCE:

Moffett, Cindy, “The Future of Product Design,” Quest, 3 Feb 2014, http://quest.utk.edu/2014/the-future-of-product-design/.

Photographs by David Luttrell.

Learn More

Learn more about Aoukar’s product design, and visitAoukar’s Kickstarter campaign at tiny.utk.edu/aoukar.